Campaign design team

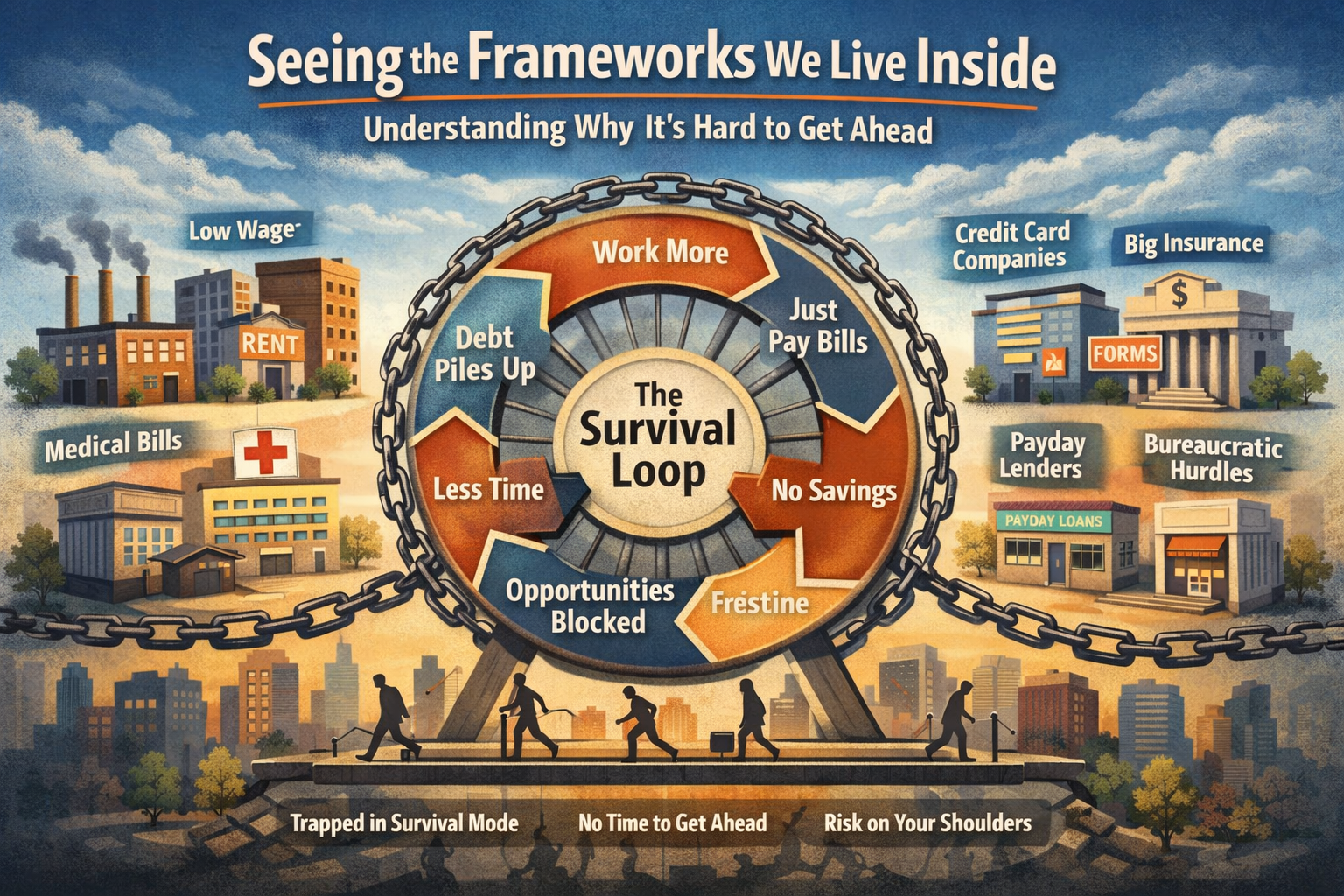

Why So Many Americans Feel Stuck—and Why That Feeling Isn’t a Personal Failure

By Vincent Cordova | December 29, 2025

Most people in the United States are not lazy, uninformed, or unwilling to work. In fact, Americans work some of the longest hours among developed nations, yet millions still feel like they are constantly one step away from financial collapse. This isn’t because people are doing something wrong. It’s because many are living inside frameworks they were never taught to see.

A framework is simply a system of rules, incentives, defaults, and constraints that shapes outcomes over time. Frameworks don’t require malicious intent to cause harm. They work quietly, consistently, and impersonally. Once established, they influence behavior whether people agree with them or even understand them.

When large numbers of unrelated people experience the same pressures—working more, owning less, feeling exhausted but never secure—that pattern deserves examination. Patterns are signals. They tell us that the issue is structural, not individual.

Survival Mode Is a System Outcome, Not a Mindset

“Survival mode” is often described as a psychological state, but in reality it is an economic condition created by design. Survival mode exists when income barely covers necessities, when emergencies turn into debt, and when time is consumed managing risk instead of building a future.

In such a system, people are not rewarded for long-term thinking. They are rewarded for endurance. Planning becomes risky. Rest feels dangerous. Change feels destabilizing. The system doesn’t collapse people all at once—it keeps them just functional enough to continue participating.

This is why advice like “work harder,” “budget better,” or “make smarter choices” feels hollow to so many. Effort still matters, but frameworks determine how far effort can travel. When effort only maintains survival instead of creating momentum, frustration is inevitable.

The Invisible Loop Many People Live In

Many Americans live inside a repeating loop that looks like this:

- Income covers basic needs.

- Little or no margin remains.

- An unexpected expense appears.

- Debt fills the gap.

- Debt requires more income.

- More income requires more time.

- Less time prevents advancement.

- The loop repeats.

What makes this loop powerful is not cruelty—it is consistency. A system that requires constant motion just to stay in place does not feel oppressive at first. It feels “normal.” Over time, however, exhaustion becomes the baseline, and people begin to internalize outcomes that were never truly under their control.

Defaults Matter More Than Intentions

Most people assume systems are neutral unless someone is actively abusing them. In reality, defaults decide outcomes far more than intentions.

In the United States:

- Housing defaults to renting before ownership.

- Healthcare defaults to billing before care.

- Employment defaults to instability through at-will rules.

- Debt defaults to compounding interest.

- Assistance defaults to complexity and re-certification.

None of these require bad actors to function. They simply require rules that prioritize efficiency, revenue, or risk transfer over human stability. When these defaults stack, they quietly shape lives.

Once defaults are set, most people don’t opt in—they are born in.

Why These Frameworks Persist

Frameworks that keep people in survival mode tend to persist for three reasons.

First, they produce predictable revenue streams. Debt payments, rent, premiums, and fees are reliable. Stability for individuals is unpredictable. Systems favor predictability.

Second, they shift risk downward. Individuals absorb emergencies, volatility, and failure, while institutions remain insulated. This makes the system appear resilient, even when people are not.

Third, they fragment time and attention. A population that is constantly busy managing survival has less capacity to question structure, organize collectively, or demand redesign.

These are not conspiracies. They are incentives playing out over decades.

Understanding Comes Before Correction

Before any system can be corrected, it must first be understood. Attacking institutions or naming entities before people see the framework often creates resistance. People defend what they believe is normal, even when it harms them, because unfamiliar change feels dangerous inside an already unstable system.

Education changes that dynamic. When people recognize that their experience is shared, patterned, and structural, blame shifts away from the self. Clarity replaces shame. Curiosity replaces defensiveness.

Only then does the natural next question arise:

“If the system works this way, who designed it? Who maintains it? Who benefits when it doesn’t change?”

That question is far more powerful when it comes from the public themselves.

The Role of Institutions (Named Carefully, Not Emotionally)

Frameworks do not appear on their own. They are shaped over time by policy, regulation, lobbying, and institutional momentum. Organizations such as the Federal Reserve influence monetary conditions that affect debt and asset ownership. Large asset managers like BlackRock and private equity firms like Blackstone participate in housing and infrastructure markets that prioritize returns over access. Business lobbying groups such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce shape labor and wage policy discussions.

Naming entities is not about assigning villainy. It is about accountability and transparency. Systems are built by people and organizations, and systems can be redesigned by people and organizations—when the public understands what needs changing.

Why Public Understanding Is the Real Force

History shows that lasting change does not begin with institutions. It begins when the public understands the problem well enough to demand better design. Laws, markets, and norms follow understanding—not the other way around.

When people see frameworks clearly, they stop fighting each other over symptoms and begin questioning structure. They stop internalizing failure and start recognizing leverage. That is when correction becomes possible.

The goal is not collapse. The goal is redesign.

A healthy system allows people to rest, recover, and build.

A broken system requires constant exhaustion just to survive.

What Comes Next (When the Public Is Ready)

This conversation does not end here. It begins here.

Correction only makes sense after comprehension. Reform only works after recognition. And accountability only matters when people understand what they are holding accountable.

When the public sees the frameworks clearly, they become the force that makes change unavoidable.